I’m aware that it has been some time since I last wrote a post. I don’t know how this spring has been like in other parts of the world, but here in the UK it has been pretty miserable and it is only just getting warm and sunny. Which means that I have been hit by one nursery bug after another and I spent nearly the entire May sick and miserable. This isn’t supposed to happen in what I basically consider summer!

But there will be more coming in the future. So if you are new to Good Evidene, why not subscribe so you don’t miss a new installment?

Today, I’m going to geek out and tell you about my (two) favorite academic papers by Caroline Hoxby and co-authors that try to understand the reasons for the lack of poor students at elite universities1. Caroline Hoxby came to present this project at Warwick when I was doing my Ph.D. and it changed my perspective on the kind of work I wanted to do. Let’s hope you love it as much as me!

The reason I love this paper so much is not just because of its content. But also because it shows that if you take the time to fully understand the problem, you may find your assumptions were all wrong. And that if you look quite carefully you can find pieces of low-hanging fruit that can make such an incredible difference to people’s lives.

So what’s the problem this paper tries to solve: Universities have long been criticized for being dominated by people from high-income and high-education backgrounds. And the better the university, the more it is the case.

It is therefore unsurprising that within the US, this problem is one of the worst at the Ivy League universities. The latest data shows that 5 of the Ivys have more students from the top 1% in terms of income than from the bottom 60%. And it’s even worse for the students from the bottom 20% - there are only 700 of them out of the more than 17000 students overall.2 And this doesn’t seem to have changed much over time.

Universities will claim that they are already doing their best to attract more students from diverse economic backgrounds. Most Ivy League universities have extensive bursary schemes meaning that many poor students end up spending less money going to an Ivy League university than if they went to a community college.

So what is keeping poor students from elite universities? This is clearly a complex question that everyone will have an opinion on and with many important causes, from structural inequality, cultural factors, and discrimination to rising university fees.

1. Asking the right question

I have seen many papers and research projects that try to tackle this question and they usually drown in the complexity. What I love here is that the authors take this fact and this complex problem and narrow it down to this simple but somewhat surprising sub-question: Do we have such few poor students in the Ivys because not more get the grades to get in, or because students don’t apply?

Most people, including those working in university admissions offices, would think that it is a question of poorer students not getting the grades. Depending on the way you view the world this could be a sign that the world is working or that the world is failing, but few people would have thought of asking this question.

I remember Professor Hoxby saying that when they asked admissions officers how many students from the bottom 20% they thought had good enough grades (which they define as having SAT scores in the top 10%) were out there, the officers felt there were very few they aren’t aware of. Maybe, maybe they thought, a couple of thousands that didn’t end up applying max.

So the researchers gathered information on all SAT scores, students’ income levels, and which universities they applied to and attended. And they found that there were at least TWENTY-FIVE THOUSAND. 25 000 students from the poorest 20% had grades that were good enough to get into Ivy League universities - universities whose graduates belong to the highest earners in the country - but didn’t apply. Remember, there are only around 17000 places!

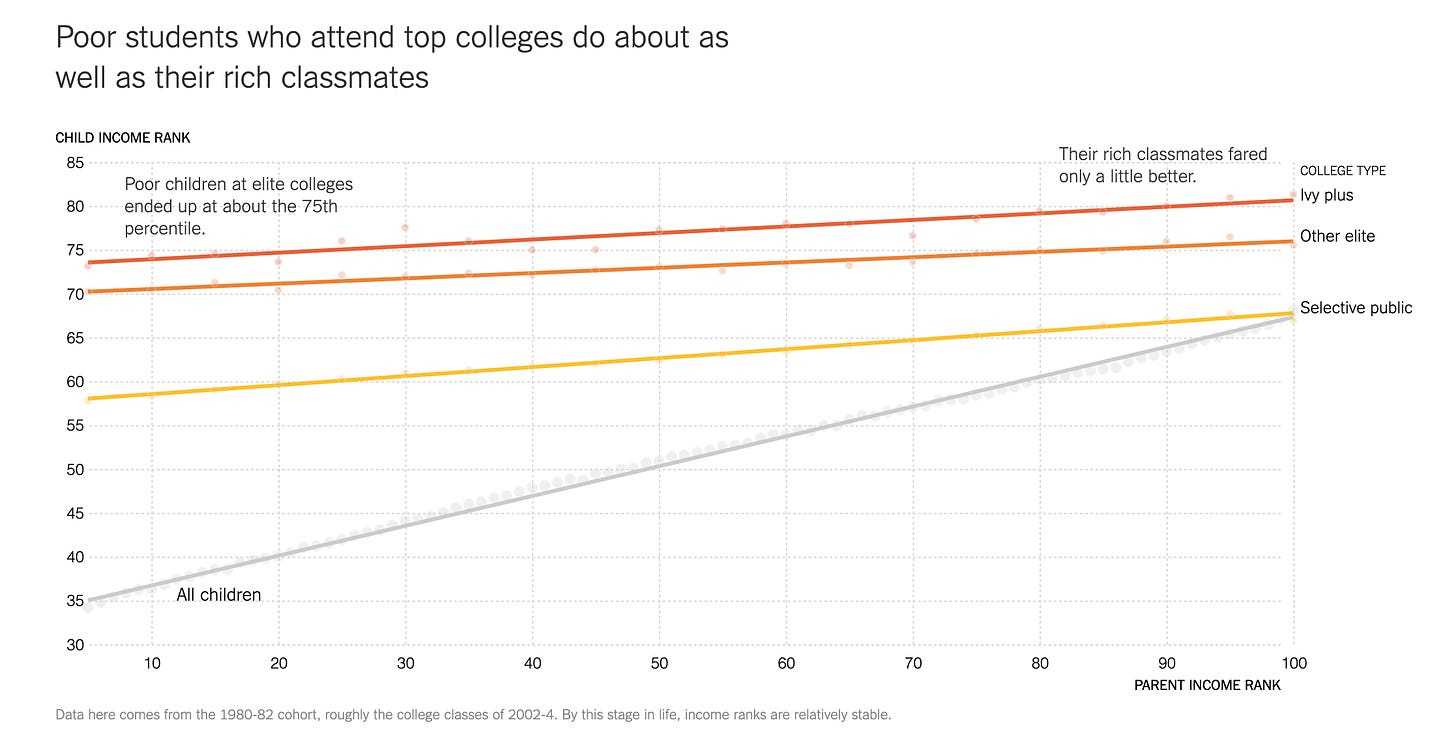

This means there is a huge opportunity to increase social mobility, especially as the researchers found that poor students that ended up attending those universities ended up doing equally well as their richer counterparts (see graph below). Anyone who thinks that in order to increase diversity in elite universities means we need to lower standards should think again.

It also shows that even people who you might think of as experts - the admissions officers in this case - may not fully understand what is going on. I’m not blaming them, but it does show you that trying to understand the problem you are trying to solve means more than asking the people affected.

2. Digging deeper

So what is keeping these students from applying? They are clearly intelligent, hard-working, and motivated, otherwise, they wouldn’t have gotten these grades.3 We could come up with many stories for this, but let’s look first at what else the data can show us.

The researchers found that poor students more generally have a very different application pattern than rich students. Rich students tended to apply to colleges that match their SAT score quite closely in addition to a few safety schools and a few aspirational schools, that they are less likely to get into. Poorer students in contrast tended to apply to schools that were often completely unselective, such as community colleges, some state schools, and some for-profit schools.

But the researchers dug even deeper and found something really interesting: The pattern only held for poor students that were in isolated locations where few others had similar grades or had gone to an Ivy League university. Poor, high-achieving students that were in towns and schools that saw a lot of high achievers on the other hand applied to the same kind of universities as rich students with similar grades.

What could be the difference between poor students in isolated and non-isolated areas? There could of course be many. It may be that those students can have access to better universities closer to home. Or maybe, the researchers thought, they have more information about what it is like studying at an Ivy League. Maybe they heard from others or through their guidance counselor that their scores are actually good enough to get them in, that they will be unlikely to have to pay fees, and what a difference going to an Ivy League university could make to their future.

This possibility is really exciting because a lack of information is something that we can change cheaply. If it is some sort of structural factor, that is usually hard and expensive to solve. But information - that could be relatively easy. Maybe, I mean there must be a reason why it wasn’t happening yet, but maybe. It’s an exciting possibility to think about.

Designing and testing a solution

The data that the researchers had was really great, but it could only get us so far to be sure what’s going on. But the case it made was so successful that it allowed the researchers to raise funds for a huge randomized control trial, i.e. one big experiment where they randomly select people to get impacted by a policy.

Another reason that I like about this paper is that the researchers designed something that could be a real policy. An actual policy that is scalable and cost-effective? This never happens in academia! (It does happen, but it should happen so much more!).

The intervention they designed was a semi-personalized information pack that was sent to each student and a waiver for the submission fee - the total package costs an average of 6$ per student. The pack gave them information about the likely fees they would pay, and graduation rates, provide links to online resources, and told them about deadlines and how to apply for financial aid. They also have a version targeted at parents.

You may wonder, could the students not have simply found this information online? The paper is of course 10 years old, but at the time the researchers observed that “…the information available [online] […] tends to assume that low-income students are low-achieving and gives them guidance that corresponds to this assumption.” Doesn’t that just make you feel great about humanity?

I won’t go into all the details but they randomly select a group of high-performing poorer students to get these information packs and then check what happens to them compared to a control group. Being an academic paper it is set up not just to

And this intervention seems to have a big impact. Students that remember seeing the material are 78% more likely to be admitted to and 46% more likely to attend a university in line with their SAT scores (i.e. an elite university, given their high scores).

The fact that what they trial only costs 6$ per student means that the benefits vs costs of this intervention are incredibly high. The main alternative policy that has been explored is in-person counselling, which is even more effective but you know, costs 600$ dollars per student.

Why I love it

There are so many things I love about this paper but particularly that it shows what a difference really good evidence can make for policy making:

They don’t just ask the “experts” what the problem is, and make great use of data that already existed but no one really looked into (since then this has changed, and the NY Times has a really great dashboard that I took some of the graphics for this article from).

It shows that really understanding the problem is so important when you want to come up with a solution.

Their process emphasises external feedback. I didn’t cover this here but they ran a few pilots that allowed them to tweak the intervention. I talk about best practice on this here.

If there is one message for policy makers from this to take away is not to trust what you think the problem is, but challenge yourself to look at what the evidence actually says.

Hoxby, Caroline and Sarah Turner, "What High-Achieving Low-Income Students Know About College,"The American Economic Review (P&P), 2015.

Hoxby, Caroline and Christopher Avery, "The Missing "One-Offs": The Hidden Supply of High-Achieving, Low-Income Students," Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 2014

This isn’t just a US problem. Two weeks ago, I reviewed a report from the Royal Economic Society that found that 1 out of 3 students that studied economics at the best universities is male, white and from a higher socioeconomic background. One in three!

What about money you may ask? Ivy League universities are famously unaffordable but I already mentioned that these students would be unlikely to have to pay any fees and their housing is often subsidized. As a result, those that attend non-selective colleges end up paying more including accommodation and fees combined than those attending Ivy League schools - though this may not hold for those that can continue living at home.